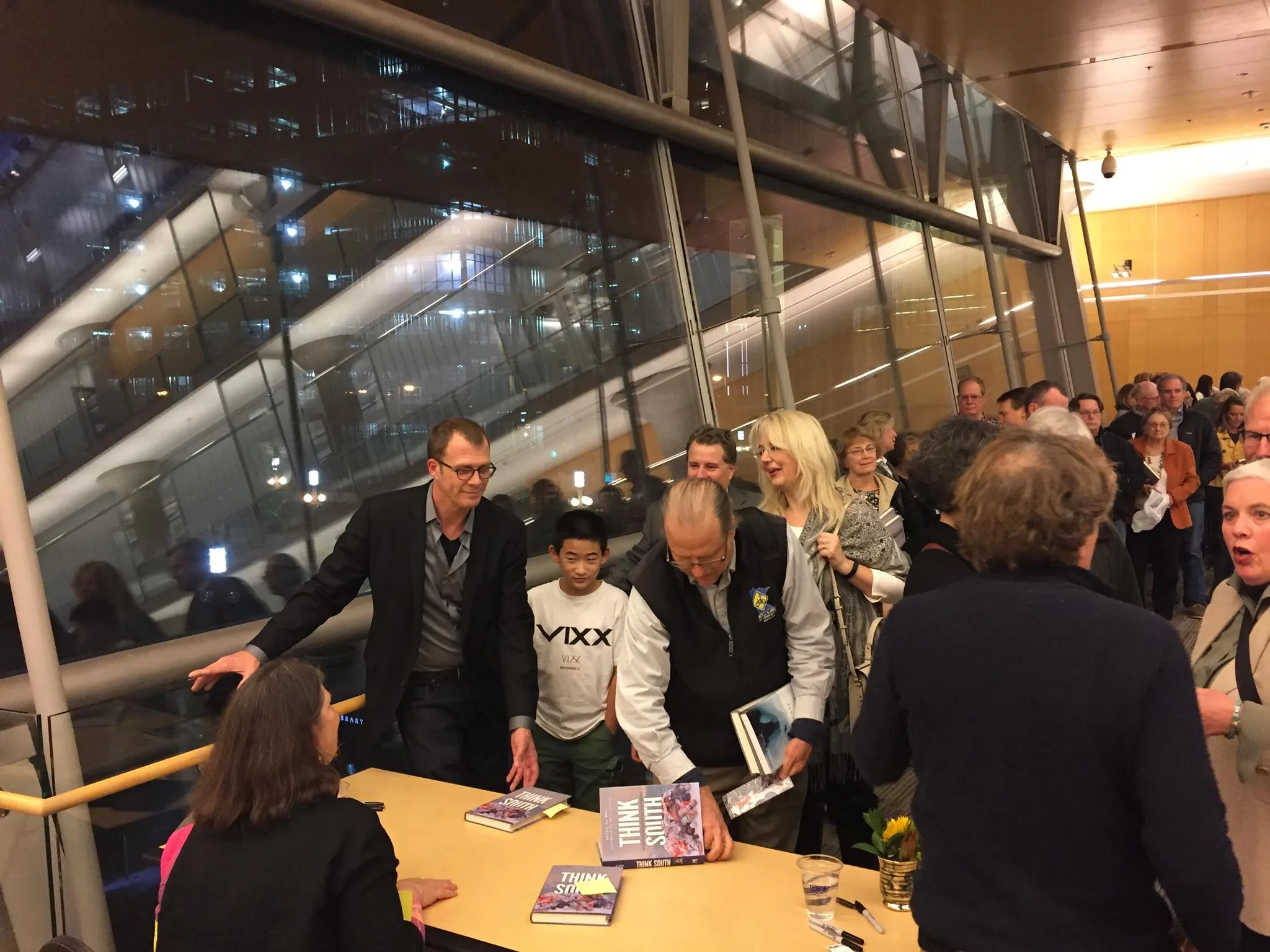

While celebrating the launch of my new book Think South last week, I happened upon several people who followed the book's subject, the International Trans-Antarctica Expedition, as kids. I met them not, as I anticipated, in the audience, but in various roles surrounding the event. One of the reporters who called for an interview told me she'd followed the expedition in a Minnesota school many years ago, and a guy on the film crew chronicling this, the 25th anniversary of the expedition, said it had been an important part of his childhood in China.

Certainly, we gave kids lots of opportunity to learn about this historic crossing of Antarctica back in 1990. Over 10 million children from around the world followed the adventure via hotlines, curricula, television broadcasts, Weekly Reader, museum exhibits, China's Youth Daily, National Geographic, and on and on. When the expedition finished, these kids had new heroes, an enriched understanding of Antarctica's importance, and a vital new cause - saving the environment.

Back in those days, however, the ozone hole had just been discovered, and dire predictions about the world's changing climate were inexact. Trouble was brewing, we knew, but it seemed far away and abstract. The expedition's goal was to make the kids care. But the call to action was unspecific and the danger probably a little like the scary bogeyman in the closet, imagined but unseen. As a result, kids were passionate about "saving the world" without knowing what that meant. They sent letters to their Congressmen and carried placards in parades. But none of us knew how to guide them (and ourselves) to practical solutions that could stem the tide.

Now these very same kids are grown into a world where evidence is mounting that the change is upon us. My own children are among them. Passion and good intentions are insufficient. Now adults, this new generation must research, invent, and advocate for the millions of small and large changes that will minimize the damages. They must break this overwhelming global problem into pieces that allow each of us to act within our own lives and permit institutions and governments to drop the theoretical debate and collaborate... the inspirational replaced by the practical, the passion translated to action. They are the climate generation* and they must tell us what to do.

Are they up to the task?

The other day, we heard from a teacher whose fifth grade class followed the Trans-Antarctica Expedition twenty-five years ago. Not only did the experience change her way of teaching, she told us, but five of the girls in that single classroom went on to earn PhDs in science, their interest attributable directly to Trans-Antarctica. They are the future. The kids that followed us are now replacing my generation as the ones in charge, and their readiness to tackle the big stuff makes me proud and gives me hope. They will do it for us, the helpless, waning generation, and, most importantly, they will do it for the generation to come - their children.

There were several of this third generation in the audience the other night - young kids, listening to the expedition's stories, meeting the heroes that once so inspired their parents. They will, I hope, take for granted the need for change for which their parents are fighting. My own grandson, at eight years old, stood reverently in line for autographs and, his mother tells me, carried his copy of the book to bed. I am so awed and grateful for his sense of wonder. I only hope we've set the stage and told the story well enough that when it is his turn, he will understand inherently what is the right thing to do.

*Will Steger, leader of the 1990 International Trans-Antarctica Expedition, created a foundation to support young people's action and advocacy for climate solutions. Click for more information about the Climate Generation, a Will Steger Legacy.